The Legacy of Ruth Asawa

Explore the impact of female Japanese American sculpture – Ruth Asawa on education in the arts, the challenges she faced and the inspiration for her intricate wire weaving techniques.

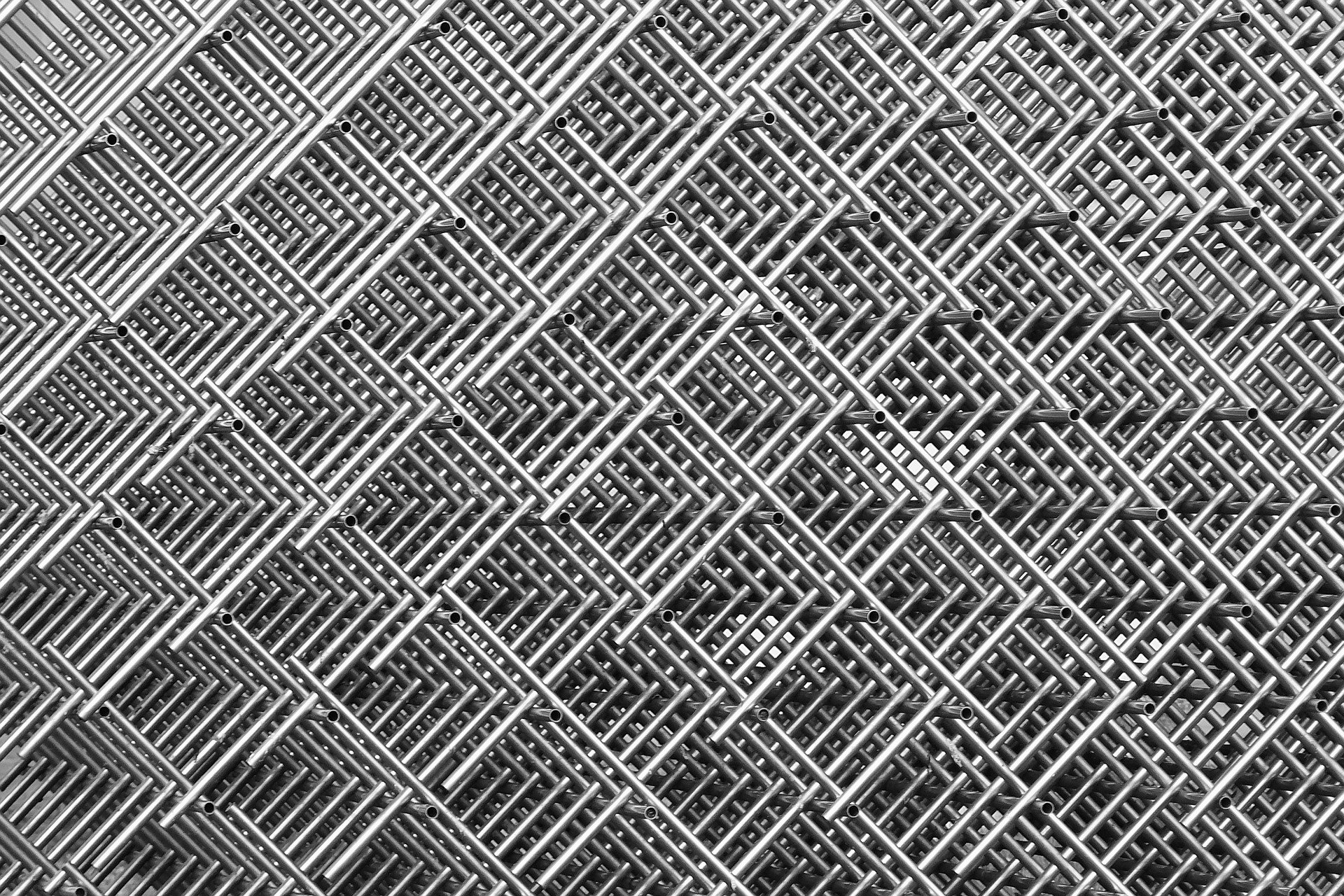

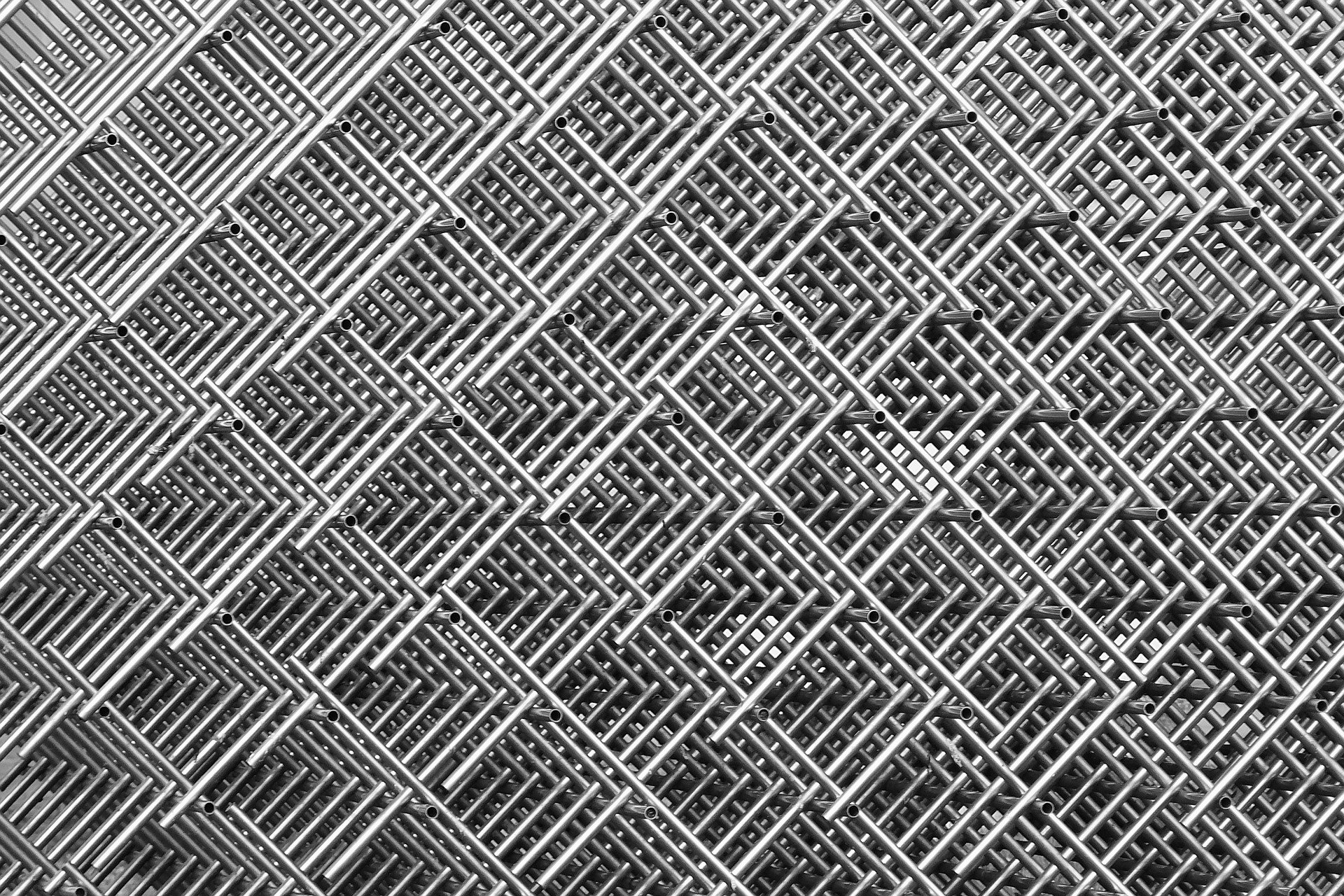

Ruth Asawa was a hugely talented and influential Artist, devoted activist, and tireless advocate for arts education. A Sculpture of Japanese American decent, Asawa was best known for her extensive body for hanging wire sculptures. Born in Norwalk, California in 1926 to first generation Japanese immigrants Umakichi and Haru Asawa. Asawa showed an aptitude for art at an early age. On Saturdays she attended a community Japanese language and cultural school where she practiced calligraphy. Although Asawa had hoped to attend one of two prominent art schools in Los Angeles—the Chouinard Art Institute or the Otis Art Institute—World War II and the signing of Executive Order 9066 changed everything.

In the hysteria following the outbreak of World War II, the United states government feared that Japanese Americans would commit acts of sabotage against their country. Although no such act was ever committed by a Japanese American, some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were removed from their homes and made to live in internment camps. In February 1942, Ruth’s father Umakichi, a 60 year old farmer who had been living in the United States for over forty years, was arrested by FBI agents and taken to a camp in New Mexico. Ruth was only sixteen years old when her father was separated from their family for the next six years.

Incarceration and Art, working with wire

In April, Ruth, along with her mother and five siblings was sent to the Santa Anita race track in Arcadia, California, where they lived for five months in two horse stalls. She used her free time to draw. Among the internees were animators from the Walk Disney Studios who taught art to their fellow camp inmates. When September arrived the family were sent to an internment camp in Rohwer, Arkansas where Ruth continued to spend most of her free time painting and drawing. It is not typical for artists to begin their careers in incarceration, but despite the hardship, Asawa not only absorbed lessons from her time in camp she first learned weaving as a volunteer camouflage net maker, and picked up the sumi brush during art classes – she flourished.

The Rohwer Relocation Center, surrounded by eight watch towers and barbed wire fences, held eight thousand Japanese Americans. ‘’There were lined for everything’’ Ruth recalled. ‘’ I believe half of our time was spent waiting in line’’.

“I found myself experimenting with wire,’’ Asawa explained: “I was interested in the economy of a line, enclosing three-dimensional space without blocking it out. I realized that I could make wire forms interlock, expand, and contract with a single strand, because a line can go anywhere.’’ Following her release from Rohwer in 1943, she applied and was admitted to the Milwaukee State Teachers College on a scholarship sponsored by the National Japanese American Student Relocation (NJASRC) There she studied drawing, painting, printmaking, and jewelry, with the intent to become a schoolteacher.

Ruth Asawa’s Mexican influence

In 1945 Asawa travelled to Mexico City to study Spanish and Mexican Art. While attending the Milwaukee State Teachers College in Wisconsin she was unable to receive her degree due to continued hostility against Japanese Americans. As a result, Asawa continued her education at the Black Mountain College in North Carolina. While there, she studied under Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham, and Buckminster Fuller. According to Asawa, “Black Mountain gave you the right to do anything you wanted to do.” In 1946 through until 1949 Asawa studied at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, renowned at the time for its progressive pedagogical methods and avant-garde aesthetic milieu. Here, Asawa absorbed the vital teachings and influences of Josef Albers, Buckminster Fuller, and Merce Cunningham, as well as weaver Trude Guermonprez. It was at Black Mountain that Asawa began to explore wire as a medium. In 1947, Asawa returned to Mexico on a trip sponsored again by the Quakers, where she observed indigenous artist techniques for crocheting baskets, these craftsmen taught her how to loop baskets out of this material which would later inspire her to create crocheted wire sculptures.

Rebel, Mother, Artist and Activist in San Francisco

Against her parent’s wishes Asawa moved to San Francisco with her husband Albert Lanier, with whom she had six children a ubiquitous coloring page sparked Asawa’s mission. When her kids brought home an outline of a Thanksgiving turkey, Asawa realized that the public education system needed better resources in the arts — and that they should endeavor to offer richer art experiences to kids of all ages. She became a major force in founding public arts education for San Francisco children and was an instrumental part of the Alvarado Arts Workshop, the annual Music, Art, Dance, Drama, and Science (MADDS) Festival, and the 1973 federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) program. She helped found SCRAP, an art material recycling program for teachers and artists, in 1976, fearlessly defended the preservation of murals, and promoted inter-generational workshops and the vital importance of gardens. She was also central to the creation of the San Francisco School of the Arts (SOTA) High School in 1982. In 2010, SOTA was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts.

Asawa’s work and life immortalised

Her work can be seen in many outdoor locations and museums. The estate of Ruth Asawa has been represented by David Zwiner since 2017. David Zwirner – A powerful Art dealer notes, “The gallery is proud to be entrusted with the extraordinary legacy of Ruth Asawa. Asawa began exhibiting her sculptures, paintings, and drawings in solo and group shows in 1953 and has held major solo retrospective exhibits at the San Francisco Museum of Art (1973), the Fresno Art Center (1978 and 2001), the Oakland Museum (2002), the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum (2006), and the Japanese American National Museum (Los Angeles, 2007).

Her most famous public sculptures are “Andrea,” the mermaid fountain at Ghirardelli Square (1966); the Hyatt on Union Square Fountain (1973); the “Buchanan Mall (Nihonmachi) Fountains” (1976); “Aurora,” the origami-inspired fountain on the San Francisco waterfront (1986); “History of Wine” (1988), a fountain at Beringer Winery in St. Helena, the “Japanese-American Internment Memorial Sculpture” in San Jose (1994)

Asawa, in many ways, mirrors the complexity of her works. To categorize her as just a visual artist, or just a concentration camp survivor, or even as just a Black Mountain College protegeé would obscure the complexity of her life and legacy, particularly her unending dedication to arts education.

Asawa maintained an ambitious and important career as a sculptor while also fighting for a stronger role for the arts in public education–particularly in the San Francisco Unified School District. Asawa has been acknowledged in the local press as “San Francisco’s best-loved artist.”

Asawa died on August 5, 2013, at her home in San Francisco at age 87.