Medusa Art: Is Society Still Comparing Women to Medusa?

She’s portrayed as a dangerous woman; her snake-like hair a metaphor for her wicked and untrustworthy demeanour. I’m talking about Medusa, the Greek mythological figure who turns her onlookers to stone. But ancient depictions of Medusa were very different from those we see today. And she may not be as treacherous as you might think.

Is society still comparing women to Medusa, or are we finally changing our viewpoint?

Medusa’s Story

The earliest known record of Medusa and the Gorgons came from Hesiod’s Theogony. According to the author, Medusa lived with her two sisters, Euryale and Sthenno, at the edge of the world. While all three sisters were children of Phorcys and Ceto, only the Gorgon sisters Euryale and Sthenno were immortal. Medusa was said to be mortal.

Hesiod’s tale does not divulge much about Medusa, apart from the fact that she was killed at the hands of Perseus. But Ovid’s Metamorphoses gives us some more insight into her life.

Ovid says Medusa was a beautiful maiden – so much so that her beauty caught the eyes of Poseiden. His desire for Medusa was so strong that he “ravaged” her at Athena’s shrine. Seeking vengeance, Athena transformed Medusa’s hair into snakes so that anyone who gazed directly at her would turn to stone.

In the tale of Perseus and Medusa, Perseus was sent on a seemingly impossible mission to bring back the head of Medusa. Polydectes was the one who sent him on this mission, which he believed would be certain suicide for Perseus. You see, Polydectes was in love with Perseus’ mother Danae, but Perseus did not approve of the relationship.

Polydectes underestimated Perseus, the son of Zeus. He decapitated Medusa whilst she slept thanks to help from a pair of winged sandals from Hermes, a Cap of Invisibility from Hades, a bronze shield from Athena, and a powerful sword from Hephaestus.

Immediately after beheading Medusa, Pegasus, the winged horse, sprung from her neck.

Medusa’s Transformation in the Art World

If you take a look at early Medusa art, you’ll see a very different creature than the one we know today.

Greek mythology paints Medusa as a grotesque hybrid creature; part animal, part human. She had wings, boar-like tusks and fangs. Her eyes were bulging, and she sported some unsightly facial hair. These images from ancient Greek times were carved into funerary monuments and painted on pottery.

A terracotta jar made between 450 and 440 BC gives us one of the earliest examples of the classical Medusa. In this depiction, Medusa is sleeping peacefully with angelic wings folded behind her and a head free of snakes. But in a terracotta stand from 570 BC, we see a more grotesque depiction of the mythological creature, with fangs, a beard, curled hair and a deformed nose.

Things start to change for Medusa during the Classical art period. In the 5th and 4th centuries BC, her grotesque visage became increasingly feminized. Her moustache and beard were replaced by smooth cheeks. Her fangs replaced by voluptuous lips.

But Medusa’s defining feature – her snake-filled hair – doesn’t appear until much later. In fact, that invention is credited to one of the most renowned artists of all time: Leonardo da Vinci.

It is rumoured that Leonardo da Vinci painted a rendition of Medusa on a shield. The depiction was so masterful, it supposedly frightened his father. According to a 1550 account by art historian Giorgio Vasari, da Vinci’s father considered the piece macabre, so he sold it to Florentine merchants. The shield has long since vanished and may be nothing more than a myth.

Later Roman depictions of Medusa also included her snake-filled hair. Classical and Hellenistic depictions of Medusa were more human-like, but she retained supernatural details, like snakes and wings. Her facial features may have changed, but she still retained that piercing, deadly outward gaze.

Even an early 1800s plaster cast from Antonio Canova depicts Medusa with sorrowful eyes wide open. This particular representation of the mythological figure includes wings in her hair, with just a pair of snakes peeking out from her curly hair. But we also see snakes wrapped around her neck.

Medusa also appears in later European art, like with Peter Paul Rubens’ rather macabre rendition of a decapitated Medusa. The piece, called Head of Medusa, gives the mythological creature a human-like face; her lips, skin and eyes grey from her death. Her head is surrounded by snakes, although she appears to have human hair.

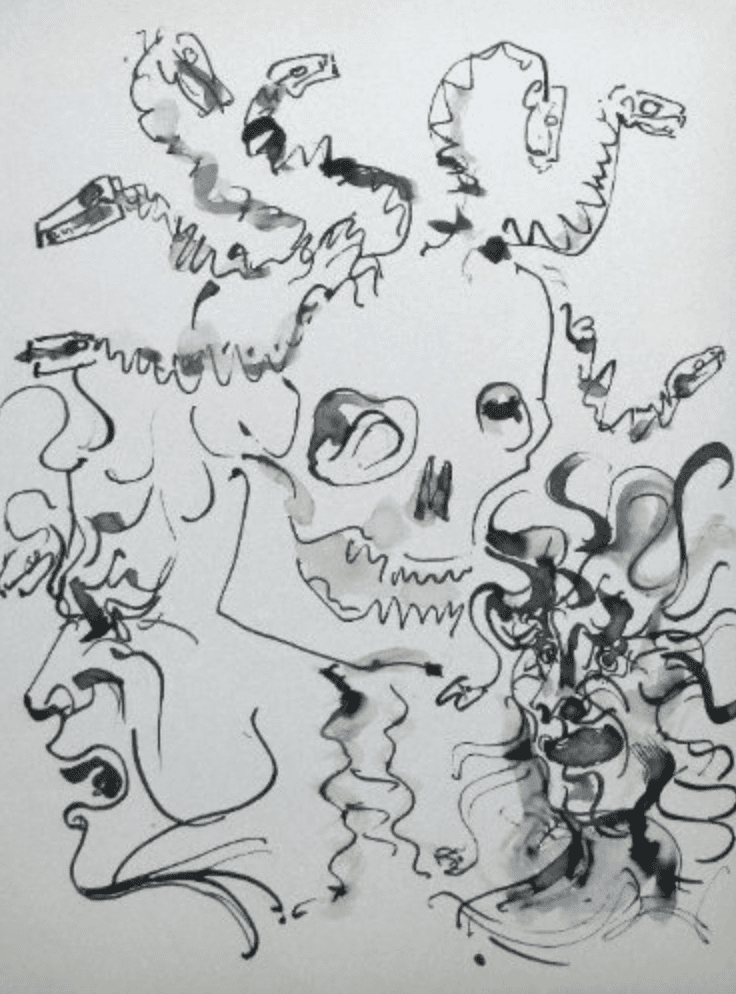

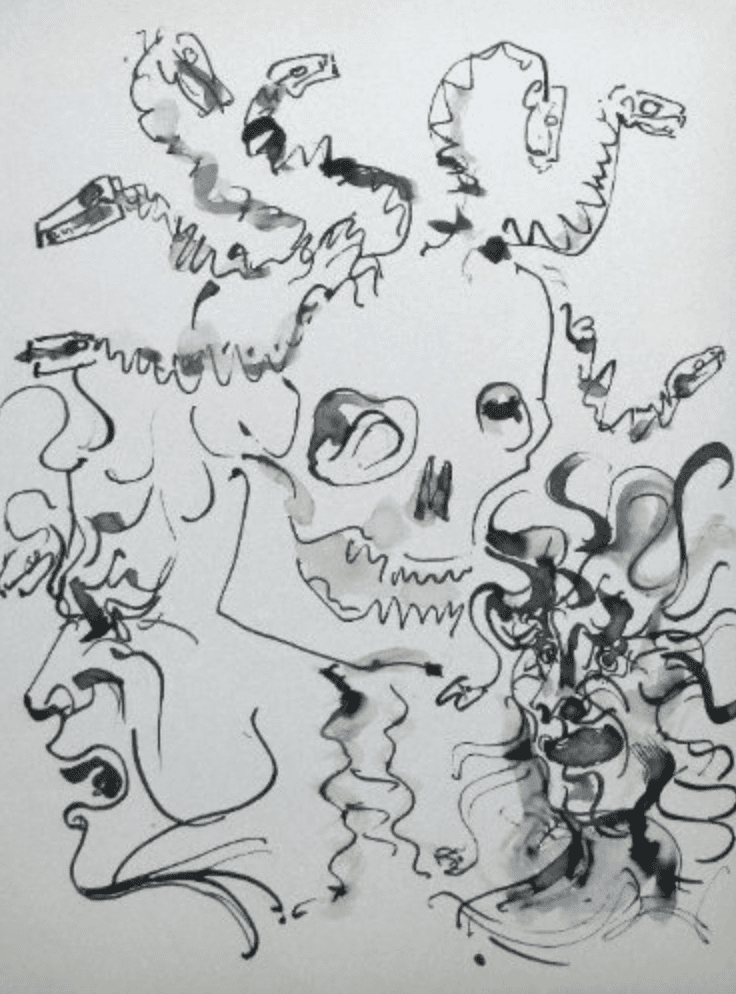

Medusa has been depicted by famous artists like Pablo Picasso, whose lithograph “Medusa” was created in 1957. In his rendition, we see the transformation of Medusa from maiden to monster. On the left is a side profile of what looks like maiden Medusa with curly hair. But as we move to the right of the piece, Medusa transforms first into a skeleton with snakes atop her head and then to the monster we know today.

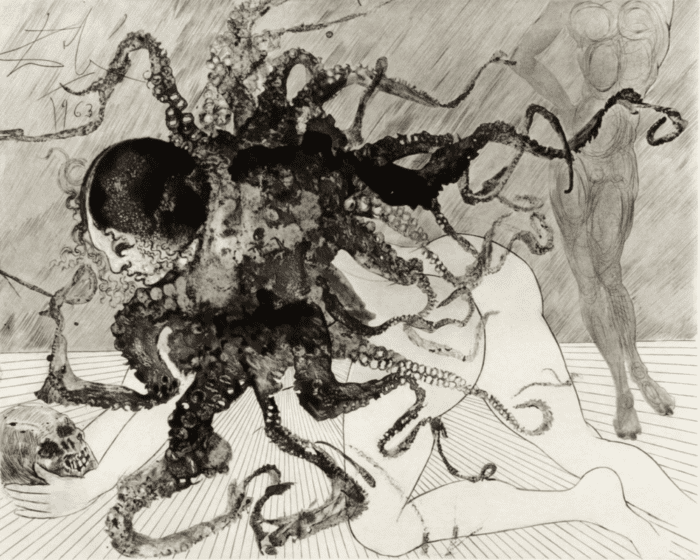

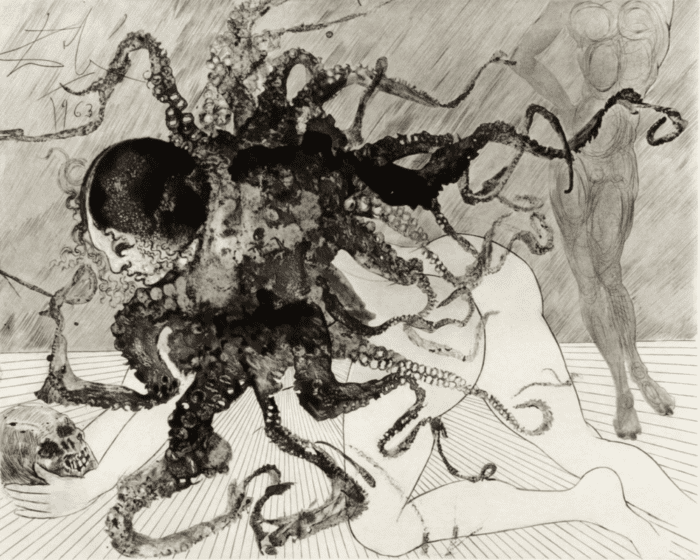

Salvador Dali took a different approach to his rendition of Medusa. He depicts her with the head of an octopus, with her tentacles dangling down from around her neck. In her hands, she holds a human skull.

While Medusa is often associated with violence, death and danger, she was also viewed as a symbol of protection. Her head was believed to keep evil away. Not surprisingly, we see Medusa’s head in numerous Greek and Roman shields, mosaics and breastplates.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art explored the transformation of this Greek mythological figure in the exhibit Dangerous Beauty: Medusa in Classical Art, which included many of the works of art we just discussed.

The Medusa Myth Paints Women as Dangerous Creatures

In painting and sculpture, Medusa is almost exclusively portrayed as a dangerous, treacherous creature – particularly in more modern renditions. Her beauty and femininity are viewed as dangerous. In fact, the majority of the hybrids (half-human, half-animals) in Greek mythology were females (e.g. sirens).

Medusa’s story and visage served to demonize women and may be considered the early version of the “femme fatale.” They reinforce this idea that women are dangerous through their looks and power.

But is society still comparing women to Medusa? Absolutely. Just look at the December 2013 cover of GQ magazine, which featured singer Rihanna as Medusa. The highly-sexualized image shows a topless Rihanna with hair made of snakes, long, piercing fingernails, and that unrelenting, deadly gaze Medusa is known for.

In the political world, the polarizing 2016 election in the United States reminded us that we still view women as dangerous “snakes.” A photoshopped version of Benvenuto Cellini’s famous sculpture of Medusa and Perseus shows Trump’s face in place of Perseus’ and Hillary Clinton’s in place of Medusa’s. That photoshopped image was plastered on t-shirts, mugs and tote bags, and sold for profit. And it serves as a reminder that society still views women as untrustworthy beings unworthy of power.